It’s a logical result of extinction, so one wonders why no one bothered to do the sum before: what happened to the world when it lost the cumulative billions of tonnes of faeces produced by mammoths, sloths and whales? A new study from the University of Vermont has shown that the planet has suffered twofold from the removal of this biomass. Not only from the lack of diversity created by the extinctions of ancient megafauna and modern, human-induced depletions of many species – from seabirds to elephants, and whales – but from what they once did for our planet by spreading their poo around, redistributing nutrients and fertilising new growth.

“The past was a world of giants,” the new paper rhapsodises, evoking an Edenic world – albeit one full of poo. Dr Joe Roman, co-author of the study, says: “This once was a world that had 10 times more whales, 20 times more anadromous fish like salmon, double the number of seabirds, and 10 times more large herbivores like giant sloths and mastodons and mammoths … this broken global cycle may weaken ecosystem health, fisheries and agriculture.”

Remove all that guano and poo from the planet and you are left with a greatly reduced fertility. The scientists behind the study estimate that the capacity of land animals to spread nutrients has fallen to 8% below its value before 150 species of ice age mammals went extinct. Until now, it was thought that animals played a minor role in the process. But the new study indicates that they acted, en masse, as a “distribution pump” (nice image, eh?), fertilising new areas that would otherwise be unproductive.

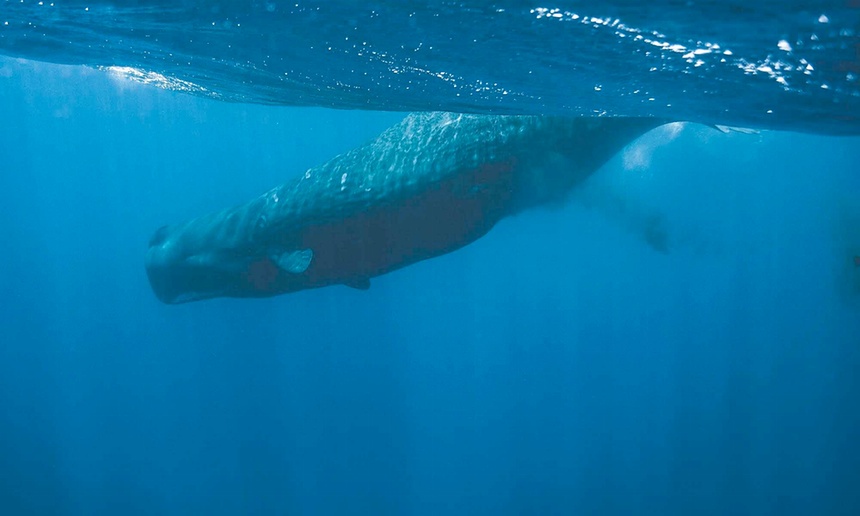

The paper is a follow-up to one that appeared last year, also co-authored by Roman, which reported the ameliorating effect that whale faeces has on climate change, fixing carbon in the oceans by fertilising phytoplankton growth. Indeed, the “Save the Whale” campaigns of the 1960s and 70s might have been retitled, “Save the World” (and thereby countered Peter Cook’s expletive-ridden Derek and Clive tirade in 1973, “They’ve produced nothing in the way of literature. All they’ve produced is a load of other fucking whales”). Last year’s much-reported scientific paper from the New Bedford Whaling Museum’s Robert Rocha and others indicated that in the 20th century alone, nearly 3 million whales were killed. The removal of such a vast volume of biomass from the Earth’s environment has had an incalculable effect.

As George Monbiot notes in his book Feral, sperm whales, the deepest diving of all whales, also stirred up nutrients from the ocean bed. Before commercial hunting, whales and other marine mammals moved 375,000 tonnes of phosphorus to the surface each year. The current figure stands at just 82,500 tonnes. There is an even greater irony here, too. In the whaling armageddon of the last century, the bones of great whales ended up being ground down for fertiliser.

But the University of Vermont’s report also speaks to our philosophical attitude to faeces. Why do we spend billions of pounds getting rid of our waste – other than out of a strange hatred of our own bodily functions? Imagine what all those lost nutrients could do – not least in generating bio-responsible power. Our modern disassociation from poo speaks volumes. In the past, human excrement was a vital part of the food chain, with “night soil” regularly used to feed the ground – and thus the plants that we, or our animals, ate.

During the 19th century, the gathering of dog poo for the tanning industry was a specific trade, somewhat paradoxically known as pure finding.

Imagine, too, in a pre-combustion engine city the size of London, New York or Paris, the volume of horse manure being produced each day. Characteristically, the great horse manure crisis of 1894, when it was predicted that London’s streets would be overwhelmed by dung – was precipitated by the invention of chemical fertilisers, thereby creating a whole new set of problems for the environment. Now we can barely bring ourselves to mention the subject. But without poo, we would be nothing. Funny how it takes mass extinction to remind us of that fact.

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/oct/28/attitudes-poo-life-on-earth-mass-extinction-bodily-functions?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other